Charleston’s Dirty History

Charleston and its surrounding communities sit at the center of a unique estuarine ecosystem, shaped by four tidal rivers and the daily rhythm of the tide. Our creeks and marshes are home to skimmers, pelicans, dolphins, redfish, oysters, and shrimp. We can fish, swim, and paddle just minutes from where we live and work. Our community often appears on “best of” lists and ranks among the top in the United States. But there’s a dirty secret beneath the surface.

From the beginning, Charleston has struggled with sewage treatment and water pollution, leading to significant public health problems. In the 1800s, the city faced dysentery and typhoid outbreaks from contaminated drinking water, and cases of hepatitis linked to oysters harvested from polluted waters.

The Long Road to Sewer Infrastructure

On the Charleston Peninsula, disposing of waste in the streets was banned, leading to the use of outhouses with cesspools and underground privy vaults to collect human waste. Years of poor maintenance and outbreaks of yellow fever, dysentery, and cholera led the city to build a tidal drain system. These drains allowed residents to channel waste into a set of canals that filled with water on an incoming tide, and then dumped raw sewage into Charleston Harbor on an outgoing tide. Unfortunately, the tidal drain system and privy vaults proved ineffective at controlling disease outbreaks.

In the United States, dirty water is not just an environmental issue or a public health issue, but it is also an environmental justice issue. Lack of access to safe sanitation has disproportionately impacted racial minority communities in the United States due to factors such as racially segregated neighborhoods and barriers to funding for infrastructure improvements. Charleston residents were disproportionately exposed to these pathogens which resulted in a greater likelihood of death for black children compared to white children in Charleston during the era of privy vaults.

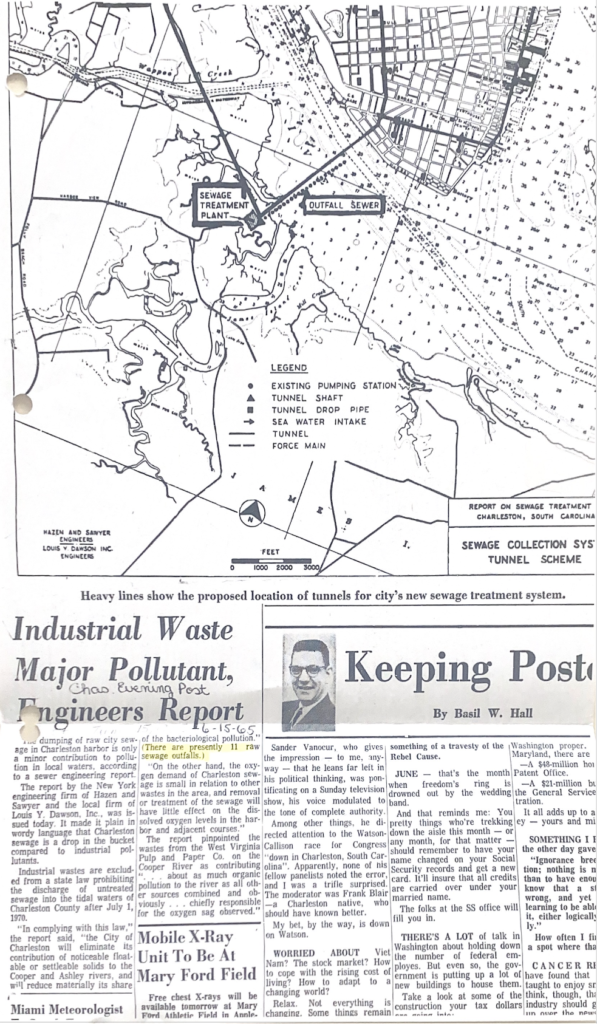

In 1894, construction of a sewage collection system began on the peninsula south of Broad Street. Over the next 40 years the system was extended to other parts of the peninsula. Even after the sewer system was finished it still dumped raw sewage into the harbor without any treatment. Dumping raw sewage into the harbor remained legal until 1970 when it was prohibited by the Clean Water Act. The Plum Island sewage treatment plant was completed in the early 1970s.

Plum Island discharged partially treated sewage into the harbor until it achieved secondary treatment capability in 1984 and full compliance with Clean Water Act standards. Image to the right shows a newspaper article from 1965 showing proposed location for the Plum Island Sewage Treatment Plant.

Early suburban growth in communities around the peninsula was supported by septic systems and sewage lagoons (now banned by the EPA). Like privy vaults and tidal drains, these methods of sewage treatment polluted nearby creeks and rivers. Today, James Island Creek and other local waterways still suffer from high levels of fecal bacteria, septic tanks are a major contributor.

Infrastructure Under Pressure and Bacteria on the Rise

In 2021, water samples from the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, Shem Creek, James Island Creek, and Charleston Harbor were analyzed by Dr. Michael Janech from the College of Charleston. The samples contained DNA from pathogens like tuberculosis, staph, cholera, and E. coli. While the presence of DNA from these pathogens doesn’t necessarily cause illness, it raises concerns for swimmers and other recreational users, especially those who are immunocompromised.

Despite the known problems with septic tanks, new developments on Johns Island, and in Mount Pleasant and Awendaw continue to be proposed, approved, and built with septic tanks.

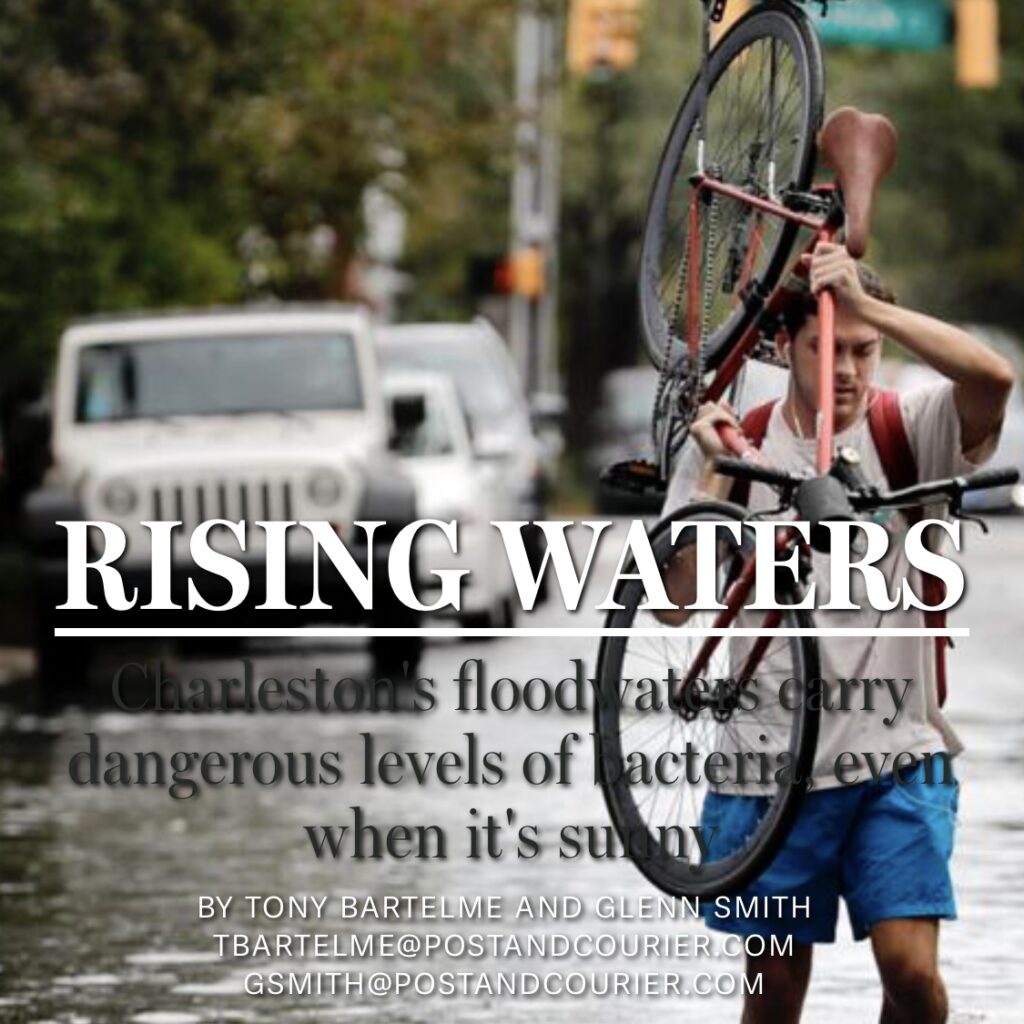

Bacteria and pathogens are not just present in local waterways, they’re also found in floodwater. College of Charleston researchers found fecal bacteria levels in floodwaters far higher than what is considered safe for swimming and recreation. These hidden bacteria come from various sources, including wildlife and pet waste, and most notably, septic tanks and sewer overflows.

While some see floodwaters as a playground, bacteria-laced floodwaters are becoming more common in Charleston. The Post and Courier sampled sunny-day flood waters during high tides near schools, hospitals, and residential areas, and found bacteria levels well above state safety guidelines. With sea levels rising, sunny-day floods—caused by high tides—are predicted to become more frequent, increasing the risk to public health.

Historical data and models show that Charleston experienced about two flood days per year in 1950, compared to 25 days per year in 2014, with predictions of 60 days per year by 2051. This increase in flooding means that the likelihood of bacteria exposure and related health risks will only grow, highlighting the importance of fighting for cleaner waterways and ongoing water quality testing.

Taking Action

Despite Charleston’s dirty history, we have the power to change our fate and become stewards of clean water for future generations.

Know before you go. Check Charleston Waterkeeper’s Swim Alert data to see where it’s safe to swim.

If you have a septic tank, have it inspected by a professional, regularly maintained, and pumped out to ensure it is working properly.

Talk to your city and town council members about why clean water is important to you and your family. Tell them you support sewage and floodwater infrastructure upgrades that protect public health and water quality.

Want to learn more? Read this…

References

Barbot, L. J. (1890). Public Health Papers and Reports, American Public Health Association: Tidal Drain System of Charleston, South Carolina.

Bartelme, T., & Smith, G. (2018, June 14). Charleston floodwaters are crawling with unsafe levels of poop bacteria. Post and Courier. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/charleston-floodwaters-are-crawling-with-unsafe-levels-of-poop-bacteria/article_9a120c08-5780-11e8-b5eb-4b448c32fc94.html

Bartelme, T., & Smith, G. (2020, October 1). Charleston’s floodwaters carry dangerous levels of bacteria, even when it’s sunny. Post and Courier. https://www.postandcourier.com/rising-waters/charlestons-floodwaters-carry-dangerous-levels-of-bacteria-even-when-its-sunny/article_1e4536a0-0353-11eb-8304-7fb4057a8d15.html

Charleston Water System. (n.d.). Wastewater Treatment. Retrieved August 25, 2024, from https://charlestonwater.com/168/Wastewater-Treatment

Clean Water Act, Pub. L. No. Chapter 26. Retrieved August 25, 2024, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/33/chapter-26

Foster Farley, M. (1973). The Mighty Monarch of the South: Yellow Fever in Charleston and Savannah. The Georgia Review, 27(1), 56–70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41396925

Kryston, A., Woods, C. G., & Manga, M. (2024). Social barriers to safe sanitation access among housed populations in the United States: A systematic review. In International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health (Vol. 257). Elsevier GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2024.114326

Leland, J. (1983, August 3). Century-Old Drains Uncovered in Charleston. Post-Courier.

McCray, S. (2022, May 28). Tuberculosis, other potential human pathogens in Charleston waterways, CofC study finds. Post and Courier. https://www.postandcourier.com/environment/tuberculosis-other-potential-human-pathogens-in-charleston-waterways-cofc-study-finds/article_0ca9157c-dce8-11ec-a633-67da55930c53.html

Moftakhari, H. R., AghaKouchak, A., Sanders, B. F., Feldman, D. L., Sweet, W., Matthew, R. A., & Luke, A. (2015). Increased nuisance flooding along the coasts of the United States due to sea level rise: Past and future. Geophysical Research Letters, 42(22), 9846–9852. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL066072

Morris, J. T., & Renken, K. A. (2020). Past, present, and future nuisance flooding on the Charleston peninsula. PLoS ONE, 15(9 September). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238770

Onley, R. B. (1896). Mayor Ficken’s Annual Review: Report of Sewerage Commissioners.

Ramsey, J. (2023, May 5). The history of human waste in Charleston’s waters runs deep. Post and Courier. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/the-history-of-human-waste-in-charlestons-waters-runs-deep/article_9ffed896-df91-11ed-9d4a-9b7a5ad9cf28.html